‘Just So’ Stories[4]

From: A Grandson’s Account of his Grandfather’s Life and his Collection of Photographs.

… an essential constancy of modern art – uniqueness of personality – persists; no longer manifested through facture, the individuality of touch, but through an unrepentant autobiographical confession or fantasy concerning those areas of human activity in which the artists are most singularly personal their literally – private lives. [Pincus-Witten 1977]

[4] Twenty-five years ago, paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould and biologist Richard Lewontin criticized the so-called adaptationist programme, charging that overeager biologists labeled some organisms’ traits adaptations without real evidence. Many traits, they said, were actually by products, associated with adaptations, but not the result of natural selection. The bridge of one’s nose will hold up one’s glasses, but it’s not an adaptation for such. This so-called science, argued Gould and Lewontin, boiled down to little more than just-so stories–referring to Rudyard Kipling’s century-old children’s fables that offered imaginative explanations for certain animals’ distinctive qualities. URL: http://www.the-scientist.com/yr2004/mar/research2_040301.html

The aim of this thesis is to explore contemporary attitudes to photography and the degree to which photography has had an affect on autobiographical memory[5]. The key vehicle for this exploration is my own studio practice which appropriates photographs originally taken by my grandfather, A.E. Ingham, some of which coincide with my own childhood and hence throw an illumine but disconcerting light on my own autobiographical memory. I propose to discuss ways in which autobiographical memory is formed, stored and retrieved, and to move on to consider how these processes have evolved through interaction with photography. The opening chapter initiates this investigation with an analysis of the subject matter of my grandfather’s collection of photography. The collection is a means by which I am able to examine the relationship between my own sense of autobiography and photographs of past events which form a part of that autobiography.[6]

[5] Autobiographical memory is a term use by researchers into memory to define a type of memory for events and issues related to a persons life. As will be shown in Chapter 2 of this thesis it has different characteristics to other types of memory. Martin A. Conway working in the Department of Psychology at Durham University explains that there is a type of memory called Autobiographical Memory and this is, ‘…a type of memory that persists over weeks, months, years, decades and lifetimes, and it retains knowledge [of the self] at different levels of abstraction, [Autobiographical memory] is a transitory mental representation: it is a temporary but stable pattern of activation across the indices of the autobiographical knowledge base that encompasses knowledge of different levels of abstraction, including event-specific sensory perceptual details, very often – although by no means always – in the form of mental images.’ [Badderley:55]

[6] Martha Langford writes: ‘As long as photography has existed, claims for its usefulness as a repository of memory have been countered by arguments that echo the ancient distrust of writing, the fear that reliance on any system of recording ultimately leads to mental degeneration, to a condition of mnemonic atrophy’ [Landgord 2001:4].

Initially, I am concerned with why, as an artist, I have been using the collection as a basis for my work and theoretical concerns. I begin, therefore, with an autobiographical approach, an account of my own childhood memories and how they connect to the photographs in the collection. Of necessity, this account is both a partial and fragmentary, and is in part informed by photographs themselves, as for example when these have triggered a further associative chain and/or network of memories. This narrative is thus written in a conventional autobiographical form, combining the ‘facts’ of my life with my own reminiscences of actual events.

There follows a biographical account of my grandfather’s life, using the written and anecdotal evidence I have been able to gather about his life, alongside my own personal recollections. It is included to make possible some understanding of his motivations for taking photographs and as a way of understanding my own interests in the collection. This biography is pertinent for the concerns of my thesis as it constructs and interprets a version of the past; as in their own way do autobiographical memory and photographs.

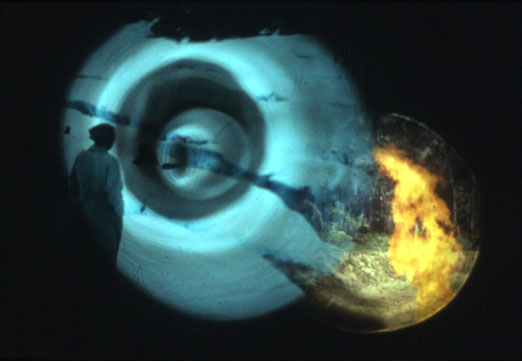

RMJI Trinidad Fire. Camera Projection. Digital Print. 67cm x 95cm. 2004

In the conclusion of this chapter I will begin to examine these two modes of description as ways of analysing and interpreting past events, and to consider how these subjective processes of recounting, themselves, can influence memories.[7]

[7] Psychologist M.A. Conway says of this, ‘When a person has the experience of remembering a past event then knowledge drawn from the phenomenological record, thematic knowledge, and the self all contribute to the construction of a dynamic representation which constitutes that memory.’ [Roberts:137]

Döppelganger: Yonder. Photographic Print 120 cm x 150 cm. 2003

1. An Autobiographical Account of My Involvement with the Collection.

This autobiographical sketch is only a partial and fragmented account of my life as it takes its cue mainly from my past experiences with the collection of photographs. I am associated with the collection in many different ways. I am directly and indirectly implicated with some of the photographs. Although I was not present when the majority of the photographs were taken, I am depicted in others and have visited certain of the locations. At other times, I was actually present at the event and recognise a number of the people photographed. I have also been in situations where the photographs were presented as transparencies in the form of slide shows. When the collection came into my possession, I already knew some of the background from anecdotal evidence given to me by my family.

An image from the collection. My grandmother in the Alps. 1960s

1.1. Working with my grandfather’s collection of photographs.

I started to use the collection as source material for my art practice in 1996. A year earlier, I made a conscious decision to change the way I worked. After making sculptural objects and site-specific installations for fifteen years, I had decided that my work had become too reliant on a given site and had become too impersonal. Reviewing my previous work, I found that mathematics was one area about which I had always been curious, but with which I had never directly engaged in my practice. I therefore initiated an investigation, both practical and theoretical, into some of the relationships between visual art and mathematics. One direction this exploration led me was to look at my family history. My father and his brother had studied mathematics at university and my mother’s brother is a mathematics teacher, I had studied mathematics at A-Level. I became especially interested in my paternal grandfather who was a professor of mathematics at Cambridge University. It was at this stage that I decided to explore my own history and the history of the relationship I had to my grandfather by using his collection of photographs as a starting point.

I was also interested in the way that some of my sculptures and installations affected certain spectators, whereby they would be reminded of events from their own past. In a few instances, this seemed to be for them like Proust’s encounter with the madeleine,[8] the work stimulating strong sensual memories. I therefore became curious about the role memory played when art works are confronted.

[8] Proust writes, ‘It is not possible that a piece of sculpture, a piece of music which gives us an emotion which we feel to be more exalted, more pure, more true, does not correspond to some definite spiritual reality. It is surely symbolical of one, since it gives that impression of profundity and truth. Thus nothing resembled more closely than some such phrase of Vinteuil the peculiar pleasure which I had felt at certain moments in my life, when gazing, for instance, at the steeples of Martinville, or at certain trees along a road near Balbec, or, more simply, in the first part of this book, when I tasted a certain cup of tea.’ [Proust 1984:44]

1.2. My childhood experiences with the collection.

In 1966 I returned to Britain from Colombia, my family having previously lived in Trinidad and Tobago, where I had been born in 1960. My mother, brother and I lived a couple of streets away from the house of my paternal grandfather and grandmother in Cambridge. It was here that I first remember meeting my grandfather. We would visit the house they called ‘Millington Road’[9] regularly, and after my grandfather’s death in 1967 I lived in this house until 1976.

[9] The road was called Millington Road and at the time still had Gaslights illuminating it. The house was always called Millington Road by all the family and visitors.

Me outside Millington Road house 1967 and Me up a tree in a Cambridge park 1967. [Images from the collection]

For many years, and long before I moved to Cambridge, my grandfather had the habit of presenting slide-shows of his trips abroad and his other activities to family and friends. When I came to Cambridge these presentations continued and I became a part of his audience. These transparencies are now the major part of the existing collection.

When I think back to these presentations, the only group of images I clearly recall followed his return from a long trip to India. I have been told that this ‘event’ was staged in the drawing room and continued every evening for a week. Each evening the room had to be rearranged, causing quite a ‘palaver’. He had made the projector himself, incorporating a wide-angle lens, made out of wood, pots and pans, and held together with nuts and bolts. It was not only able to show mounted transparencies but also un-mounted rolls of transparencies.

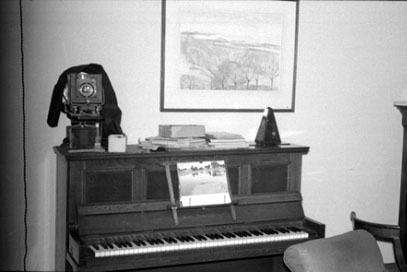

My Grandfather’s home made projector on top of piano in the drawing room in the Millington Road house. [Image from the collection.]

Detail of my Grandfather’s home made projector on top of piano in the drawing room in the Millington Road house. [Images from the collection]

The transparencies were projected onto a large, 8ft x 6ft presentation screen. The screen covered nearly all of the French windows and when not in use was stored, retracted out of sight, behind the pelmet of the curtains.

He presented the transparencies after dinner and the performance lasted about two hours.[10] While the transparencies were being shown he would describe[11], in detail, the places and people he had encountered on the trip.[12] He would also explain at length why some of the photographs were over or under exposed, or were out of focus, and what would have been there if this had not been the case.

[10] Martha Langford in her book, Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums, writes, ‘Looking at another person’s snapshots, slides, home movies, or tapes can indeed be killing: presentations are rarely short in duration, and repletion seems endemic to the genre.’ [Langford 2001:5].

[11] ‘The photographic moment and speech have much in common: visual literacy and memory less so, though they are complementary. The accumulation of photographic moments does not replace memory; rather, it overburdens recall with visual data that explodes in the retelling. That we desire to retain all that data in a permanent structure in which it can be visited, from which memories can be retrieved, fit with our faith in literacy, but challenges its rules. Our mimetic photographic memories need a mnemonic framework to keep them accessible and alive.’ [Langford 2001:21]

[12] Henry Sayre describes the slide show and the family album as “the mnemonic devices of a new oral history.” This is another way of saying that the album functions as a pictorial aide-memoiré to recitation, to the telling of stories [Langford 2001:5].

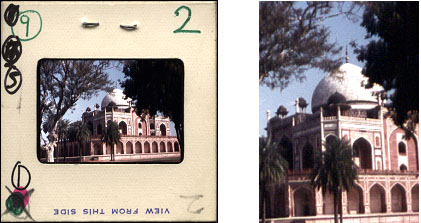

It is these incidents that have stuck in my mind most vividly. I remember one particular slide being so hopelessly over exposed, that nothing of any significance could be seen. This ‘image’ seems to have been burned into to my memory.[13] My grandfather described in great detail what would have been there, which as I recall was an Indian temple.

[13] These have been called ‘Flashbulb Memories’ or ‘Benchmark Memories’ and are often of historic or momentous events. Some researchers argue that these memories do not change over long periods of time. Although in tests these memories have been seen to succumb to the same vagaries, distortions and reconstructions as other types of memory go through. Neisser says of these types of memory, ‘…such memories are not so much momentary snapshots as enduring benchmarks. They are places where we line up our own lives with the course of history itself and say, “I was there”.’ [Roberts:136]

Indian Temple 1966. [Images from the collection] Detail

Indeed, until I started to look at the collection more closely, I believed it to have been the Taj Mahal. I have since discovered that no images of that particular palace exist in the collection. I may therefore be confusing similar images of Indian temples in the collection – or it could just be that some of the transparencies are missing.[14]

[14] There are some gaps in the collection where photographs are missing from certain verifiable sequences of images.

When I first went to these presentations, I was just six years old. I had never been to the cinema nor seen television, and therefore it was my first experience of this sort of visual spectacle. I remember, initially, being very excited. My family has over the years mythologized this particular event and other similar slide presentations. It is therefore difficult to separate what actually happened from the anecdotal reminiscences that have become embroidered over time.[15] The transparencies themselves, my own memories and the memories of others is all that I have left of these episodes.

[15] Scott McQuire writes of this, ‘What is called history is never homogeneous, made up only of positivities and positives, all that is solid, enduring, visible, memorialized and saved, but also, and as importantly, is formed by processes of selective amnesia, strategic illegibility, repression, avoidance, neglect, and loss. Recognizing that history is biodegradable, that it belongs as much to the decay of origins and archives as to their preservation and ‘museification’, demands new protocols from those which have operated in the name of absolute origins, authentic relics and photographic truths.’ [McQuire1998:176]

Furthermore, I am not sure if I am now only remembering memories of my older memories, or even remembering other people’s recounted memories of this event.[16] This seeming conundrum became one of the factors behind my interest in the influence of photography on autobiographical memory. It seemed to me there was an interesting distinction between the supposed certainties of photographs[17] as compared to the uncertainties of autobiographical memory.[18]

[16] Victor Burgin alludes to this when he quotes research made by Marie-Claude Tranger on the way people remembered certain events from WWll. She found that there was a complex relationship between everything they had seen and their memories. When talking about what she had found out she says, that there were, ‘Memories of fact [mixed] with memories of images, or of words, and even memories of memories.’ In some cases she also found that they were remembering other peoples recounted memories. [Burgin:228]

[17] Susan Sontag in an early argument in her book On Photography says of photographs that they, ‘…do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it.’ She qualifies this later on by saying, ‘Although there is a sense in which the camera does indeed capture reality, not just interpret it, photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings are.’ Susan Sontag, On Photography. Penguin Books, 1979. pp.6-7. Barthes on the other hand describes the photograph as having a, ‘..certain but fugitive testimony’ [Barthes 2000:27]

[18] Siegfried Kracauer argues that, ‘Memory encompasses neither the entire spatial appearance of a state of affairs nor its entire temporal course. Compared to photography, memory’s records are full of gaps.[Kracauer:50]

1.3. Who has owned the collection.

When I came to live at the Millington Road house, after my grandfather’s death in 1967, the collection of his photographs and his photographic equipment were stored in a cupboard in a small dressing room next door to his study. My brother and I often played in this room and took an interest in the cameras, light meters, and flash guns, but took no special notice of the photographs. I especially remember playing with his homemade slide projector. I also used his enlarger when learning how to develop black and white films. This was in his old darkroom in the attic. It was not until the house was being cleared following my grandmother’s death in 1983, that his photographs resurfaced. They passed first to my uncle and then to my brother, before being left in another cupboard in my mother’s house. I took possession of them in 1996.

Image of my grandfather’s enlarger and darkroom in the attic of the Millington Road House. [Images from the collection]

1.4. My encounters with the collection.

When I first took possession and re-encountered the transparencies, after a thirty-year gap, I started to remember the slide-shows. As I immersed myself further into the collection, I came to recall the sofa, the darkness, and the musty smell of the drawing room. The bleached out slide and the animals made on the screen with the shadows from our hands also came to mind. From these memories I started to recollect the room in detail and all the other activities that had taken place there.

Memories of my grandmother reading to my brother and I also came to mind. She would read aloud from Alice in Wonderland, Peter Rabbit, Wind in the Willows, The Hobbit and the Just So and other stories by Rudyard Kipling. I remembered my grandmother crying while reading the story of Riki Tiki Tavi, a mongoose who dies heroically in one of Kipling’s stories. And I remembered the Jabberwocky…

The Beginning?